Horse-and-Buggy Courtship at 6 Miles an Hour

FROM ALLAN STIRRATT

THERE is nothing like a fast horse and sleigh filled with fur rugs for courting, unless it’s a surrey with a fringe on top, or a buckboard hung on springs - always of course with a wise old horse for motive power. In fact there are hundreds of marriages still in existence here in Nutley that grew out of such horse-and-buggy courtship.

Allan H. Stirratt, last of a century-old line of livery men and horsemen, is an authority on horse-and-buggy courtship, because he wooed and won his own wife in a bay-powered runabout between here and Little Falls. For years, in succession to a blacksmith father and a carriage painting grandfather, he furnished Nutley swain with one-horse motive power for courting.

“Horses seemed to have a horse-sense that horsepower doesn’t have” Stirratt told The Nutley Sun at his home, 314 Passaic Ave.

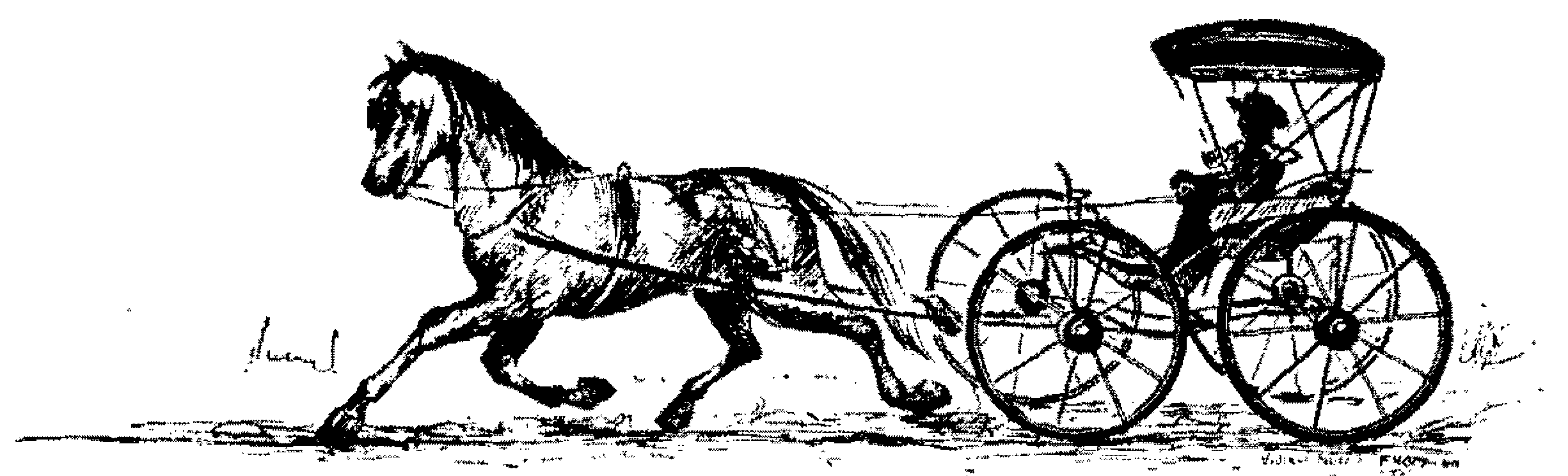

“Forty years or more ago, we had regular customers who booked certain horses once or twice a week to go courting. Sometimes they hired a sleigh when the snow was deep, or an open runabout on a warm summer night or a buggy with curtains if the winds were chill or wet; or if two couples went courting together they asked for a surrey and, of course, it had a fringe on top.

“Snow seemed to bring out a desire for speed, because nothing moves smoother than a sleigh, but it’s hard to court in freezing weather when you have to hold two reins. Nothing was better than a warm summer evening, a horse which needed no guiding and could do his six miles an hour. Our horses got so they knew the circuit to Little Falls and back.”

In that era before automobiles entered Nutley’s life, the livery stable on Chestnut Street just east of Passaic Ave., and the blacksmith shop on Chestnut Street alongside the Third River were hubs of town activity and even social centers. Mark Twain, who spent many week-ends in Nutley, as a guest of Henry Cuyler Bunner, editor of Puck, a humorous magazine of the day, loved to hunt out Joseph Stirratt, a dour Scot, father of Allan Stirratt, at either the livery stable or the smithy and discuss the problems of the day.

David Stirratt was the founder of the dynasty which catered to Nutley’s need of horses for a century. He came from Scotland, went back to bring his family, including Joseph, his son, and stayed on to die here. The blacksmith shop was one of the busiest places in town. Joseph Stirratt shod the town’s horses, David painted its carriages and a wheelwright named Simpson plied his trade along the river behind the smithy.

Stirratt horses served Nutley from birth to death. They hauled the doctor’s buggy as he raced the stork. They took the family on picnics with “Old Barney” Gannon or Jimmy Carroll sitting on the driver’s seat holding the reins. They hauled moving vans, even to New York - quite a trip in those days.

When a commuter slept overlate and missed his train, they raced six miles to Newark to catch a train. They hauled the town fire engines. They plowed the snow off icy sidewalks for $1.50 an hour, under town contract. They pulled the hack that met all trains and deposited commuters at their home for 25 cents, and finally, they hauled the hearse and the funeral coaches.

Old Barney remembered the night the stables burned. There were between 35 and 40 horses stabled there that night, well over a third of a century ago when flames broke out in the hayloft. Barney and the neighbors helped Allan Stirratt free the horses. Time after time, they went back into the smoke and flames, cut halters and brought the horses outside. Finally all were saved, but for the next few days the horses were rounded up from miles around.

In those days, the A. T. Stewart home, owned by one of New York’s “mercantile princes” stood on a vast farm on the west side of Passaic Ave., just about across from where it now stands at 314. The Stewart property ran down to the Third River and over to Centre Street. Many of the horses which escaped the fire were caught the next day in the Stewart corn fields or pastures, but others ran all over Nutley that wild night.

Barney also drove the “Penny Jigger” between the trolley car railheads at Big Tree and Joralemon Street. Public Service had won franchises from both ends between Newark and Paterson, except for a small strip between Big Tree and Joralemon. The municipality of Belleville stubbornly refused for years to grant that franchise, so Stirratt hacks carted passengers between the Paterson and Newark trolleys.

“We had a concession with Public Service to haul passengers with transfers from the trolley cars at either railhead,” Stirratt recalls. “No one could ride from Nutley to Newark in those days without riding our hack part of the way. Finally the town fathers of Belleville relented and agreed to allow the trolley lines to be connected so the hack went out of business.”

Barney used to drive, too, on the favorite excursion of Nutley sportsmen to Green Pond where the fishing was good and where there were picnic grounds. It was a 9 hour drive, at 6 miles per hour, and if there were too many picnickers, it often became necessary to change horses at Butler. It’s an hour drive today by car.

It’s a tossup whether it was Old Barney or Carlo, a huge St. Bernard, that answered all fires. In those days, Nutley had fire engines but no fire horses and agreed to pay $5 per fire to any team which arrived at Town Hall to pull the engine to a blaze.

That made a steady income for the Stirratt stable if its horses could reach Town Hall first. Many times there was quite a keen competition. Teams of horses pulling dump carts or delivery wagons were stopped in the street, when the fire alarm sounded, unhitched and raced to Town Hall to earn the $5.

That’s where Carlo and Old Barney came in, especially at night. Carlo was a huge, shaggy dog with a fireman’s heart. Stirratt rigged up a bell in the stable, hooked up with the fire alarm system. When the bell rang, Carlo would wake up Old Barney, then pick out a pair of horses and nip their heels until they woke up kicking. Barney would drop harness on them and jumping astride one horse would lead the other and race for Town Hall, with Carlo running alongside.

Carlo’s role in shortening the time that it took to get a fireengine to a blaze won for him a special collar which was the gift of the town fire department. It bore an engraved plate naming Carlo the town fire dog, and is now in the Nutley Museum.

Horse-thieves were a problem, but most of Stirratt’s customers were town people whom he or his father knew. His father was a handy man with his fists and had a hair-trigger temper. He could punish a customer who brought back an overheated horse showing signs of too liberal use of the whip. He hated to lose a horse to a horse-thief and ran them down whenever he could.

Annie Oakley boarded her circus horse, a dark bay gelding about 8 years old, with the Stirratts when she was with Buffalo Bill’s circus. It was her own horse, which she used in her shooting act and she had trained it herself.

Joe Stirratt loved fast horses and he bred the town champion, Frontier, which took on many challengers in those days when Nutley was a horsey town and enjoyed trotting and pacing races every Sunday on the Washington Avenue mile straightaway.

Frontier was sired by Sir Walkill, who enjoyed real Hambletonian blood, and bred to Stirratt’s own mare, Daisey. Sam Hopper, grandfather to the present Republican town chairman, Wilson Kierstead, owned Frontier and won many prizes with his champion.

Allan Stirratt rode in many amateur races on the old Weequahic track, long since cut up for housing, and his favorites were Queen Gentry, a pacer, and Arthur Baronward, a trotter. The horses were trained at Clifton, and on the day of a race old Barney used to lead them to Weequahic where young Stirratt drove them in high wheeled sulkies.

Allan Stirratt was seldom off the back of a horse, or pony or donkey as a boy, and he was one of the star attractions of the famous Nutley society circus, at the old Eaton Stone show ring, back in 1894 when he rode in the same program with Annie Oakley for charity, the fund being used to found a chapter of the Red Cross in Nutley.

Stirratt still has the blue silk blouse, trimmed in red, which he wore for that society circus when he put his trained pony through its paces, climbing on tubs, dancing or just galloping in a circle.

One of the Stirratt favorites was a donkey which had the vicious habit of reaching back and tearing the pants of the rider. When he ripped the clothes off Fred Brandreth one day, the Stirratts decided to sell the pet. Bunner, the editor, was looking for a pet for his daughter Nancy, so he bought the donkey which immediately reformed and became genteel.

When the first automobiles reached Nutley in the decade before World War I, the Stirratts were abreast of the times and bought a motor hack to meet all trains. Gradually gasoline took the romance out of courting and the surrey with the fringe on top was sold down the river. For sentimental reasons, a few horses and buggies were kept, but finally an epidemic of glanders hit the stable and nine of the last horses had to be taken out and shot.

From that day on, Nutley sped to and from trains, funerals, parties and picnics in motor cars.