George Washington "Slept (Near) Here," Too!

FROM FRANCIS B. LEE

NUTLEY can proudly boast that “George Washington Slept Here,” although in the interests of historical accuracy it might be better to say he “Slept Near Here.”

It all happened late in the year 1776, when, barely four months after the Boston massacre of July 4, Lord Howe had driven Washington and his troops out of New York, across the Hudson River, and forced the long retreat across New Jersey to the Delaware River. Nutley was on the line of march of the American armies and, in fact, they split here and while one part of Washington’s troops moved south along River Road to Newark and on to New Brunswick and Trenton, another column struck across Nutley and over Povershon Hill towards Bloomfield and the Watchung Mountains.

Those were dark days for the Revolution. Washington had won the first round by driving Howe out of Boston, but when they both headed for New York, Howe out-maneuvered Washington. The Americans, under Putnam, held Brooklyn. Howe massed his troops at Staten Island and then, at night, moved them across the bay and smashed at Putnam’s flank.

Washington pulled out of Brooklyn’s heights, crossed to Manhattan and dug in, but Howe followed him across the East River and laid siege. The Americans retreated up Manhattan Island and one after the other, with a loss of 2,000 men, Washington had to give up his two Hudson River forts named Washington and Lee. Finally, after the battle of White Plains, Washington crossed the Hudson and began the long retreat across New Jersey which brought him through Nutley.

With General Lord Cornwallis hot in pursuit, Washington headed for Hackensack and struck south along the river. Deciding to try and take and hold Newark, he closed on the Passaic River. The only available bridge, called “Revolutionary Bridge,” for a long time after, crossed south of Acquackanonck, as Passaic was then called.

Washington’s spies told him that the town was a hot-bed of Tories, so he took time out to send a strong force ahead to capture and protect the bridge to enable his army and its transports to cross. His spies were both right and wrong. The Dutch colonials were patriots, sturdy nationals from a land which loved its freedom. Many of the English colonials were Tories, but there were many patriots among them too.

Only one such Dutch colonist who turned Tory here ever earned mention in the regional histories and that was Abraham Van Giesen, a very wealthy land-owner whose name also figures in the early records as Van Geesen, Vangiesen or Van Giezen. All the other Dutch here, the Van Ripers, the Vreelands, Speers, Pakes, Powelssons, Rykers and Van Winkles, were patriots.

The records, incidentally, are quite confused concerning the Dutch names which often were spelled phonetically. There is mention of the Van Ripers as Van Reyper, Van Ryper, Van Reypen and Van Reipen. The Van Ripers all descended from Juriaenen Tomassen, who with 13 others received the original Acquackanonck Patent of 1684. He came from the town of Ripen in Jutland, Denmark, and using the Dutch word “van” meaning “of,” he called himself Juriaenen Tomassen van Ripen.

The Vreelands were sometimes referred to as the Jansens because they were descended from Michael Jansen, a Dutch colonist who came over from Braeckhuysen, North Brabant, in 1636, settled near Albany, and took the name Michael Jansen Van Vreelandt from the town of Vreelandt in his native Dutch province. By the time descendants worked their way south to take up land here they had dropped the name of Jansen entirely and knocked off the final “t.”

There is mention of all of them in a tattered document, yellow with its centuries of age, called: “Schedules of lands in New Ark and Surveys of lands and to whom conveyed.” It shows that before the Revolution, Nutley’s Passaic River front had been divided among five proprietors - Van Riper, Vreeland, Speer, Joralemon and King. The Van Giesen property lay west of the Third River and north of what is now Chestnut Street, and consisted of hillside orchards, woods and pastures. His home was the brown stone “mansion” which is today’s Woman’s Club.

The Van Giesen house was built between 1702 and 1704 by the same mason who built “Bend View” in 1702 for Jacob Vreeland who brought his bride there the next year. “Bend View” disappeared nearly 50 years ago when the upkeep became too costly, but in its last years, shelled in with a frame building, it was a hotel and its waterfront served as a landing place for the “Passaic Queen,” the excursion boat which ran up and down the river. Its old brown stones were bought by a Nutley builder and are to be found in more than one Nutley home of today.

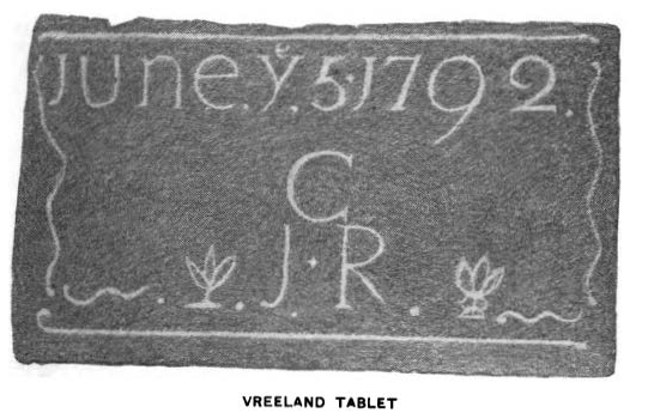

An unusual story arose when many layers of whitewash and masonry were scraped away from “Bend View” and a cornerstone was discovered at the angle of a piazza and a side wall. Set into the masonry was a tablet whose inscription was buried in the dirt of centuries. Johnson Foy, late editor of The Nutley Sun, and Mike Schultz, who lived then across River Road at “Three Maples,” washed off the tablet and finally were able to make a rubbing which gave them a surprise. The rubbing read:

It had always been believed that the old house dated to 1702, the same time as the Woman’s Club, and finally, it was the town’s conclusion that some mischievous teen-ager, sometime in the two centuries, had put a tail on the “0” and converted it into a “9.” But to get back from mischievous teen-agers to the Tories, Abraham Van Giesen was the only one who openly came out for the King of England. The Declaration of Independence had been read to the colonists at the old school house which stood on the site of the present Watsessing School in Bloomfield, and to that meeting, as well as to dozens of other meetings in and around Newark to protest the Stamp Act and the Port Bill, Nutley’s planters walked five miles or more.

When Van Giesen, as the records say, “went over to the enemy,” he shut up his house and made his way across the cedar swamps for New York. The Council of Safety, a Revolutionary committee which took over public safety affairs, moved in and confiscated the house and the land which made up a quarter of present-day Nutley.

Van Giesen himself was never heard of again, although his daughter returned and married here. When the war ended, Captain Abram Speer, a Dutch war veteran moved up from Belleville and laid claim to the Van Giesen properties which, a few years later, he sold to John M. Vreeland who made his home for the rest of his life in the house which is now the Woman’s Club.

Just where Washington and his army crossed the Passaic River will, perhaps, be disputed forever by regional historians. One school of thought places the “Revolutionary Bridge” at Delawanna, just south of the present Burch Lumber Company property. Another locates it between the high stone bridge of S-3 and Avondale bridge.

Washington’s own papers are available to support the former view, for they state that he crossed the Passaic River at Acquackanonck which enabled him to move his stores of ammunition and food to Morristown by way of Great Notch.

When his supplies were safely across, Washington moved his regiments to the west bank. Over the rude wooden bridge they tramped all one night and all the next day. It is a matter of record that before the last man was across the bugles of the approaching British army of Cornwallis were heard.

Washington had given orders for the bridge to be destroyed as soon as his army was across, so when the last straggler had reached our side of the river, a force of neighbors went to work with saws and axes and destroyed the bridge and burned the approaches.

The date of that operation is definitely set by Washington’s own recital as November 21, 1776. During the crossing, Washington’s records show that he set up his headquarters at an old Tap House on Main Avenue near the “Old First Church” which burned in 1870. In histories there is record of a letter which Washington wrote that night with a dateline of Acquackanonck.

With the British just across the river, Washington spent an anxious night there and the next morning, on November 22, 1776, passed through Nutley with, in all, less than 3,500 men, the remnant of his Army of New York. Desertions had been many and the defection of the Connecticut militia which refused to quit New England and dropped out when Washington ordered the evacuation of New York to the Jersey shore, seriously weakened the strength of the main force of the Revolutionary Army.

The road Washington used was then called “Queen’s Road,” now River Road. Provisions for the road were made in the “Fundamental Agreements” of the Newark settlers in 1666 which promised “a high way by the Great River Side and along by the Meadow.” Extended northward from Newark, following a wellblazed Indian trail used by the Lenni Lenape Indians in their annual pilgrimage to the sea to stuff themselves on salt-water fish, it was opened in 1707 and by the time Washington reached here on his retreat it was one of the main roads of the Jersey colony.

Cornwallis, pursuing Washington and finding the bridge destroyed, was not going to allow his enemy to escape and as Washington’s straggling army pushed south along River Road, the British sent a parallel column southward a few miles on the east bank of the river.

Occasionally they shot at each other and some years ago a small cannon ball was dug up from the turf of the then Yountakah Country Club and was identified as a British ball fired by one of Cornwallis’s guns at the Americans who camped for the night in the meadows which comprise now the property of Federal Telecommunication Laboratories.

The British pursuit was in two divisions; one moved from Hackensack to Rutherford and crossed the Passaic River at the stony ford where Delawanna now stands just north of the S-3 bridge, camping there for several days while awaiting the other column which, finding the bridge cut, turned north and crossed at Passaic Falls.

Cornwallis’s two columns, reunited, spent a week in and around Nutley and between Passaic and Newark, in carousing and foraging, raiding widely inland to the Watchung Mountains. They forced the unwilling Dutch to give up their grain and their cattle. The British then moved into Newark by the River Road, but as they entered the town by the north, Washington pulled out for New Brunswick. He had spent six days in Newark, divided between the camp of his army on the hill to the west of Broad Street, “along the road to Orange” and his temporary GHQ in the old Eagle Tavern, on Broad Street, just north of the City Hall.

It is a matter of historical record, too, that Nutley’s Dutch colonials emptied their larders to feed Washington’s men and horses, while Cornwallis, obliged to live off a hostile countryside, halted his pursuit for one week here and ordered his army to forage. They came and indulged in a week of revels and during that time Washington got well away.

At a point in River Road where Avondale bridge now crosses the river, Washington broke up his army. Part continued south to Newark, but he sent another column off “over the hills” towards Bloomfield, using a shortcut through the fields to reach Spring Gardens Road which it followed until it reached the socalled “back road” running from Belleville to Bloomfield.

It is a matter of record that Washington regrouped his army and fought two brilliant battles at Trenton and Princeton, both American victories. When Cornwallis closed up on the Americans near Trenton, Howe was convinced that winter would complete the task of destroying the Revolutionary Army, so he turned back to New York and left strong garrisons in Trenton and Burlington.

Washington, by that time, was camped west of the Delaware and had filled up his depleted ranks until he had a strength of 6,000 men. It was during that time that he performed the prodigious feat, with which he is credited, of throwing a silver dollar across the river.

Once his troops were ready, Washington decided on simultaneous attacks on the British in Trenton and Burlington. Once again, his subordinates failed him and with each wing out of action, he proceeded to march alone on Trenton in the center with 2400 men. Completely surprising the unprepared Hessians, he killed their German commander, Rahl, and captured 1,000 prisoners with their arms and ammunition. The crossing of the ice-filled Delaware to attack Trenton is a picture known to every schoolboy.

Cornwallis hastened with 8,000 men to Trenton where he found Washington well entrenched. Skirmishing for position, Cornwallis decided to wait for daylight to “bag the old fox,” but during the night the winds shifted and the ground froze hard. Leaving his camp fires deceptively burning, Washington circled Cornwallis’s position and, at daybreak, hit him in the rear at Princeton where he destroyed three British regiments.

Washington swept around to Morristown where he made his headquarters in a great white house which stands today as a monument to the American victory. By his victories of Trenton and Princeton, Washington galvanized the wavering colonies. Recruits flocked to his camps with Spring and the victories encouraged the French Court of Louis XVI to give the colonies its fleet and other support. The retreat through Nutley had helped make that possible.

Alas, those magnificent victories soon were nullified by popular apathy, military cabals, the disaffection of Congress and Howe’s capture of Philadelphia. Valley Forge was still ahead. It was 1778 before the British were driven out of Jersey, after the battle of Monmouth, and their going amounted to a rout as they fled ahead of the pursuing Americans. Skirmishes took place at Belleville as the British followed Washington’s escape route up River Road through Nutley to the restored Acquackanonck Bridge where they escaped across the river in darkness.

While the British camped in New Jersey, held New York and were in possession of Staten Island, Nutley and the farms of the Passaic Valley suffered almost constant raids. Crossing the meadows, the British and German troops stripped the isolated farms of their harvests. Cows and sheep were driven off and the Hessians often walked off with pigs under their arms. Too often, the defenseless Dutch and English anti-Tory farmers were wantonly murdered in defending their property.

When the terror reached a peak, the Councils of Safety in Nutley and Belleville decided to enlist a company of militia “for the defense of the frontiers.” A guard house was set up in Belleville, along River Road, near the old red stone Dutch Reformed Church.

Most of the Nutley farmers joined the “river guard” and took turns at patrolling the banks to keep off the British raiding parties. As the British roamed along the east bank, the “river guards” hid in the bushes and took pot shots at them. Often the raiders were accompanied by “refugees” as the Tories were called who had fled the region and joined the British in New York and were sent back to lead the raiding parties.

It is a matter of record that John Vreeland was one of Nutley’s “river guards” and his two huge brass-mounted pistols, marked “J.V. 1776” have been handed down in the family. There is evidence, too, that he used them lethally at least once. Firing across the river, at a point where the S-3 bridge now crosses, the young Nutley “river guard” hit a raider. He could hear the British soldier moaning in the bushes across the stream and conscience stricken he mounted a horse and rode off to get a doctor. When he returned, he led a small party across the Delawanna ford but they found the British raider dead from a Vreeland bullet.

The records show that Abram Speer, who was to figure so prominently in town history in years to come, was a captain in the Second Essex Regiment of Militia, stationed at the guard house in Belleville with his company to “guard the river.”

Speer’s father, a Dutch blacksmith who had his forge where the Belleville bridge now crosses the river, is credited with a magnificent show with an old muzzle-loader. Sitting in a church steeple, probably the Dutch Church which still stands, he shot a raider across the Passaic. The raider turned out to be an English officer going from Paulus Hook to Morristown. His watch, an English bull’s eye, was presented to Speer for his marksmanship and was also handed down from one generation to another in the family.

It was after his demobilization that Captain Speer, the blacksmith’s son, came up to the Third River and in the blacksmith shop of a Nutley smithy named Wouters fell instantly in love with the blacksmith’s daughter when she brought him his dinner.

The setting of that idyllic match was near the water cress springs at the foot of Povershon Hill where the blacksmith shop stood, at the present intersection of Centre Street and Bloomfield Avenue, and there Wouters built, as a part of his daughter’s dowry, the stone house which stands today and into which Captain Speer moved with his bride when he sold the confiscated estate of Abraham Van Giesen.