Commuting by the Erie in the Old Days

FROM FRED YOUNG

PROGRESS and luxury have softened up the commuters, for there were times in the memory of living commutation riders when a trip to New York involved real hardships, icefloes in the Hudson with bergs as big as a city block or strikes which compelled the commuters themselves to put on overalls and fire the boilers to keep up steam enough to reach Jersey City.

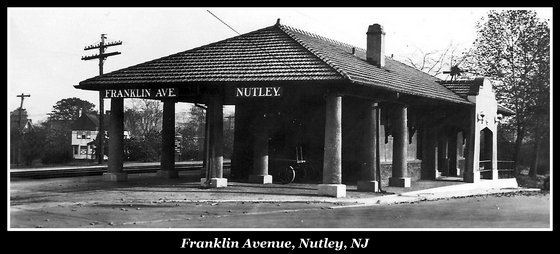

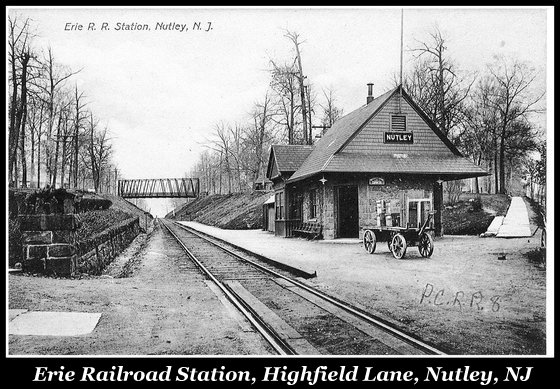

From Nutley it is possible to look across the meadows and see the skyline of the big city, but there have been times in history when the whole commuting population, which at times numbered 2,000, was marooned here for days at a time by accidents, strikes or storms. And any old commuter will tell you that our weather has changed and winters are nowhere near as hard as they were forty or fifty years ago.

Fred Young, former mayor, is one of those commuters who is convinced that something has happened to the cycle of seasons. He can remember being marooned on an ice-berg in a paddlewheel ferry, quite involuntarily of course, as the sheet of ice, a city block square, raced toward the Narrows in the swift current of the Hudson.

“In my own life, I have seen the seasons and commuting change,” Young told The Sun.

“In these days of family automobiles you can reach midtown New York through the Lincoln tunnel in fifteen minutes, and most commuters travel that way or by bus. But there was a time when Nutley had but one way of reaching New York, and that was by Erie through the tunnel to Jersey City and by Chambers Street or 23rd Street ferry to the big city.

“Nutley was a commuting town in those days, 40 to 50 years ago, when several thousand people headed for New York to work every day. The trains would be almost empty when they pulled into the Nutley stations but they were full before they reached Belleville. The morning express alone used to take 200 every day.

“Billy Berg, Stephen Dorr, and the other Wall Streeters used to catch the 8:26 train to reach the financial district by 9 o’clock. There were no chair cars on those democratic trains and Berg and Dorr used to have to take their chances on getting a seat. As soon as they sat down they opened the Herald or the Times to the financial sections, and their day’s work had begun.

“That was before the days of the tabloids, but you knew your men by the papers they read. The Herald in James Gordon Bennett’s day was the top paper, but the World was the favorite of the early version of today’s ‘stenog.’ In the evenings, on the return trains when the news and candy butchers went through the cars before the trains quit Jersey City, the New York Sun was the only paper anyone bought.

“Nutley schools were at their low point about then, and quite a few families sent their boys to school in New York. That was how I became a commuter at 8 years, along with my brothers Roswell and Philip. We went in every day to a choir school at Trinity Church.

“Naturally, we boys were delighted when tugs would have to break the ice in the slips to let the ferry boats out. We were delighted, too, one day, when the 23rd Street ferry, bucking the icefloe, hit a huge flat cake of ice. The paddle-wheeler was going so fast that it climbed right on top of the ice and lay there with paddles flying. The stern deck was level with the water and we were being carried along in the current when the ice-cake broke and let the ferry back in the water.

“Even before we reached Jersey City, snowdrifts in the meadows used to stall the commuting trains, particularly around Harrison. It was nothing for service to be delayed 24 hours during the winter, and when it did, there was a second Nutley in either the Northwestern or the Walcott hotel, the handiest to the ferries.

“There were trains all day long and late into the night. Many Nutley families used to commute to Broadway. It meant taking the 6:45 p.m. train and getting home at about 2 a.m. It was quite the thing in those days to have a spot or snack at Delmonico’s after the show, so the theatre special used to leave New York at 1:26 a.m. which gave everyone plenty of time to empty a bottle of champagne. The baggage-master used to go through the train, very thoughtfully, and turn out the oil lamps so everyone could sleep until the train reached Nutley.

“The baggage-master was a sort of master of ceremonies. On the evening commuting return trains, whist games were in order from the time the trains were boarded at the ferries until Nutley was reached. The baggage-master had his regulars for whom he held seats in the smoking car, even turning back seats to make room for a foursome. He provided cards and set up what served for a table, and in return his grateful passengers used to chip in $1 each for him every month.

“The trip was just as it is now, with the dog-leg run into Newark, but the elimination of the tunnel at Jersey City cut the run from 34 minutes to 26 for the express trains. It also cut down on the Nutley laundry bill, because the old tunnel was lined with soot.

“Travel was cheaper, too. If you bought a commutation ticket which cost $5.20 a month for the ordinary traveler, or $3.60 for the schoolboys, the ferry ride cost nothing. Otherwise the ferry cost 3 cents. Even when the Hudson tube was opened, many commuters and most of the boys still rode the ferry because in every season, that ride across the Hudson was worth all the bother-even in winter when ice was so thick along the shore that you had to walk a plank to get on the ferry.

“It was hard traveling in those winters, but some trains had a pot-bellied stove red-hot in the last car and we boys used to cluster around it. It was a great improvement when ‘pinch gas’ replaced the oil lamps. The baggage-master used to go along with a lighted taper, open the domes and light the gas lamps.” Apparently, no Nutley commuter ever was killed on the Erie. There never was a serious accident to a commuter train, but none of the old commuters has ever forgotten the wreck of the old milk train which isolated Nutley for several days until a shuttle train backed up from Jersey City and took them back to work.

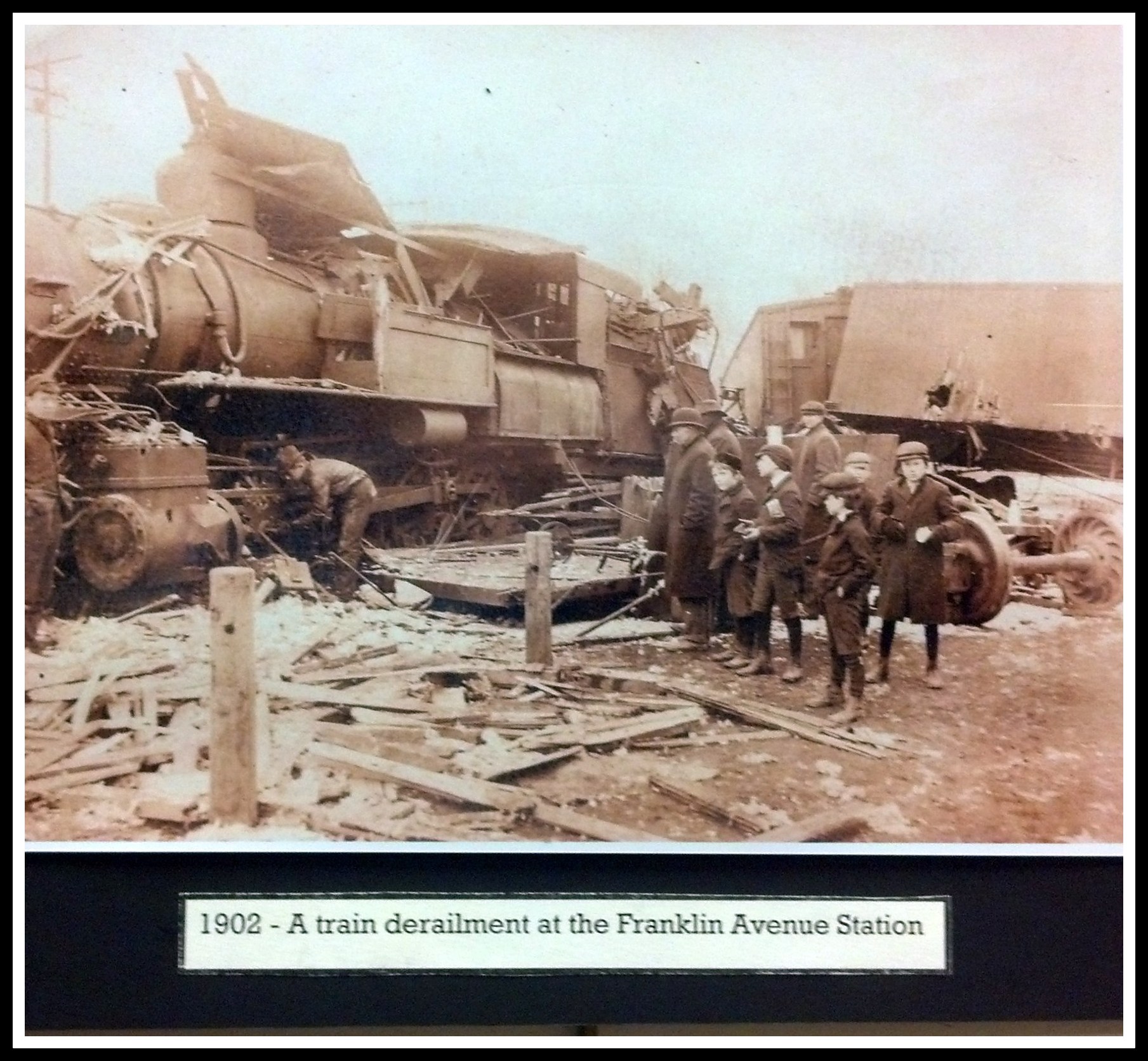

The milk train used to race through Nutley at 60 miles an hour, carrying New York state milk and cream to Newark and Jersey City. One night, about 1902, a long freight, slow in obeying orders, was in process of pulling into a siding at the Franklin Avenue station. The engineer discovered that his train was too long for the siding and several cars hung out on the main line.

He had started to cut his train and back several cars on another spur when the milk train roared down through Nichol’s cut. The locomotives met head-on at the station. Nutley people who heard the crash had to wade through cascades of milk to reach the victims.

In telescoping each other, at the great speed, the two locomotives sheared off the cabins. The engineers on both trains were killed. It took two days to clear the tracks and Nutley’s commuters had time to tend their gardens.

Another such accidental interruption of commuting occurred when a wooden trestle near the La Monte paper mill, bringing the outlet from Nichol’s pond, caught fire from burning brush and burned down. But even though it happened nearly 50 years ago, the great strike of railway firemen is still fresh in the memory of many commuters.

“Service was completely interrupted when the firemen went on strike in 1911, but the commuters got tired looking across the meadows at inaccessible New York, and did something about it,” Fred Young recalls.

“We organized a group of volunteers who motored to the Erie yards at Waldwick, near Paterson, where we took off our good clothes and put on overalls. We stoked the locomotives and got up steam. Union rules were more lax then than now, and once we got up steam the engineers took the trains out.

“It was quite a lark for us young fellows who took pride in our muscles, but it was quite a workout to keep steam up as far as Jersey City. It is quite a knack to fire a boiler correctly. We used to toss our shovels and half the coal ran off the tenders.

“I recall stoking a train on the return trip one night. I wanted to get off at Nutley, so I was not interested in getting up too much steam. But at Belleville, I had let it get down too low and we couldn’t make the grade from Belleville to the Walnut Street station. We had to back up, fire away, wait and try again several times before we made it.”