A Dour Scot Changed Nutley’s Whole Way of Life

FROM FRANK SPEER

THE Duncans brought with them from Dunfarmline, in Scotland, an era for Nutley, the era of the mills. They brought work and they brought wealth although in the end the once-thriving industry collapsed from its own over-expansion and today there remain but Town Hall and four Duncan homes as monuments to an exciting era.

There is but one direct descendant of the clan left alive today - a 92-year old widow, Mrs. Millie Duncan Mayhew, who now lives in Tudor City, in the shadow of the new United Nations building in New York City. In Caldwell lives William Duncan’s widow, the last of the indirect descendants.

Born in Franklin Avenue, the daughter of Henry Duncan, Millie Duncan left Nutley in 1889 when she was married to Charles Jackson at 21. Her husband was killed in an automobile accident near Chicago and she married again. One of her treasures which she has kept with her in all her travels since she left Nutley is a quilt made in 1825 from pieces of silk handkerchiefs made in the first Duncan mill located on the Passaic River banks at the foot of the present Grant Avenue. The block printed handkerchiefs were also used as mufflers by the dandies of the day.

Henry Duncan, the first of the clan to come here, was born in Fifeshire, in 1776, and in his native Scotland raised sheep. It was there that he learned to judge the quality of wool which later dictated his life career. He was 47 years old and a family man, with 10 children, when he decided to come to America.

Henry’s wife, Mary Livingston, was a close relative of Robert R. Livingston, a New York merchant, who was appointed the first Governor of New Jersey and was also one of five men named to a committee to study the form for the Declaration of Independence. Others with Livingston on the committee were Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and Roger Sherman. The name Livingston was carried on in the family as a surname for a second generation son.

Henry’s and Mary’s family, which reached North Belleville, as Nutley was then called, in 1823, consisted of: Isabel (born 1800), Lawrence (1802), William (1804), Sebastian (1806), Robert (1808), Jean (1810), John (1813), Elizabeth (1816) and Magdaline (1818). Mary, the baby, died in 1821 in her second year.

Henry Duncan, a dour old Scot, died here at the age of 70 in 1846, after having started the mills on their way to fortune. He had been a wool buyer for the mills and, having taken a fancy to peanuts, always carried a bagful around with him. As he haggled over the price of wool, he chewed his peanuts and dropped a few shells into the wool.

Old Henry Duncan built his family homestead on the knoll where the town library is now located, a main house and an annex. It was not only to serve as a nest for the vast brood before the children married and built homes for themselves, but eventually it became the center of the vast Duncan mill enterprises which were located in the present Town Hall and spread into what is now the Oval.

The homestead was rented out after the Duncans left and when the schoolboard ran short of rooms, the homestead became a school. Later it was torn down.

Isabel married Henry Whittaker, a rather famous surgeon in the English army before he came to this country, which accounts for the notation, “A native of England,” carved on his tombstone when he died in 1838. The Whittakers built a great rambling house at the corner of what is now Chestnut Street and Hamilton Place. The great house in time became the Central Hotel. It was torn down for a two story brick building which is now used as a warehouse.

Lawrence put up the family’s first factory here in 1834, the Duncan and Cunningham plant along the Passaic banks which turned out the first block printed silk handkerchiefs made in this country. He built a home north of what is now Grant Avenue from which he could see his factory, and like all the Duncan homes, he surrounded it with hemlocks.

In his written memoirs, Silas Chappell recalls having started to work for Lawrence Duncan in the handkerchief factory in 1835, when Silas was barely eight years old. The work-day was from 6 :30 a.m. to 6 :30 p.m., 12 hours for the pay of 25 cents - $1.50 a week. “Mister Duncan was a severe taskmaster for whom to work,” Silas recorded in his memoirs.

William, who was 19 when the family reached Nutley, was tending sheep as a boy in Scotland when a stranger fell into conversation and invited him to Glasgow to learn a trade. He went to the capital, but did not stay there long and went next to the Rainsbottom works in England to learn block printing. His contribution to the Duncan family fortune here before moving to Fall River, Mass., and from there to Staten Island, was the creation of a plant for block printing, built opposite where the Elks Club now stands on Chestnut Street.

Like his father and his brothers, he built where he could see the mills from his windows. His home stood where the present Franklin School now stands. He married Catherine Benson, daughter of William and Mary Benson, of Belleville, and their sons, Livingston (1828) and Henry (1840) joined the mills as partners when they reached 22 and carried on during the heydey of the Civil War.

Millie Duncan Mayhew is a daughter of Henry. Her father, one of the town’s few Democrats, was treasurer of Franklin Township for 10 years and was an active elder of the Dutch Reformed Church and superintendent of its Sunday School. Sebastian Duncan was also an elder and Robert a deacon in the same church.

Sebastian, or “Bastie,” who became the town’s first postmaster on July 17, 1849, built a home where Kal’s establishment is now located so as to overlook the family mills which stood where the Lobsitz Mills now stand. Across the valley, John Duncan built his home at the corner of Harrison and Prospect Streets so that he, too, could overlook the mills.

John branched out into a new field and opened a grist mill where Bloomfield Avenue crosses Centre Street, damming up Bearskin Brook to create a pond. The construction of his dam was faulty and it leaked too much to keep the waterwheel turning, so a sluiceway was built back toward Bloomfield Avenue to direct the water into an iron pipe to the waterwheel. The mill pond was favorite playground for several generations of Nutley boys. Filled in later, it is now the setting for many homes.

John Duncan once lived in the stone house built in 1812 by John Mason and now owned by Walter A. Schaefer. The Mason cotton mill had been located alongside Cotton Mill pond, now “the Mud Hole.” The property is reached by a lane which the Schaefers call Calico Lane, to perpetuate the tradition of the calico that came from the busy looms of the cotton mill, but in Duncan’s day the thoroughfare was called Rag Road.

Of the Duncan girls, Jean, or Jane as she was called, married George Poirrier. They lived in a house which still stands, back from the street, on Passaic Avenue, between Chestnut Street and The Enclosure. Poirrier succeeded his brother-in-law Sebastian Duncan as the town’s second postmaster in 1859 and moved the post office to his home. When he died in 1864, the government named Jane Duncan Poirrier postmistress.

Elizabeth married twice, first to Joseph Baldwin and then to Augustus Taylor.

Magdaline married John Rutan and had the distinction of having the only island home in Nutley. That was brought about when the Third River was divided to provide a raceway to get a swifter stream of water for the waterwheel of the Duncan Mills in Harrison Street. The Rutan stone house stood on the island between the raceway and the Third River, reached by a bridge and the yard was filled with sugar pear trees. The barns were up towards the Plenge farm.

A century ago, most of the people of Nutley were dependent for their living on the mills or the quarries. The mills were those of the Duncans or of J. B. Stitts. The lowering of tariffs against imported woolens by the Grover Cleveland administration in 1884 destroyed the mills’ business and made of Nutley an impoverished place with silent stilled spindles.

From the handkerchief factory at the foot of Grant Avenue, the Duncans moved to Yantacaw Brook, as the Third River was called, and built a cotton goods mill where the river runs under Vreeland Avenue. A boiler explosion that killed two workers named Mandeville and Tucker was followed by a collapse of the chimney, and, finally, the mill caught fire and burned.

The family’s next venture was a mill, north of Chestnut Street,along the river which the brothers Livingston and Henry Duncan built. They bought skeins of wool in Philadelphia and Trenton and wove them into plaid linings for overcoats.

Livingston and his father, William Duncan, started the Essex Mills which are perhaps the best known because the main mill building has survived in the present Town Hall. They began building in 1852 and when the Civil War started, creating a demand for woolen blankets and for blue woolens for uniforms, the mills were enlarged at a cost of $75,000.

The Essex Mills hired a hundred hands and had five sets of cards, 1,600 spindles and 28 looms, all steam operated. Pay was good during the war boom, $5 to $7 a week for six 12-hour days, but when the war ended, the mills turned with difficulty to peacetime production. The mills turned out green coverings for billiard tables and even paisley shawls, rated the best made in this country.

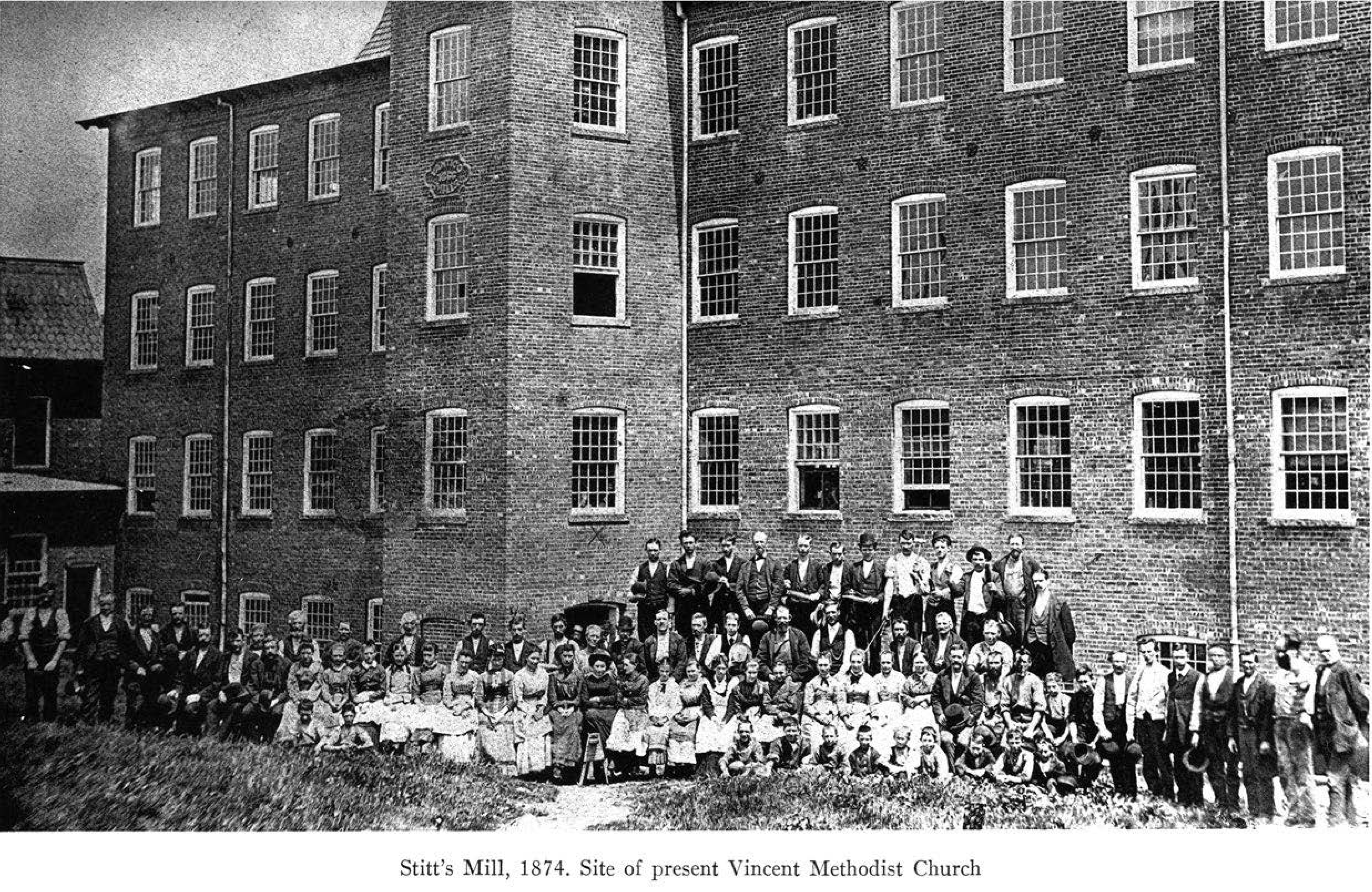

John Stitts built his rival Yantico Mills alongside the Essex Mills, separated only by a road. The Stitts Mills were three stories high in brick, but disappeared when ground was cleared for Vincent Methodist Church which later rose on the site.

Another Duncan venture was the Harrison Mill erected in 1840 along the Third River at Harrison Street and operated by the three sons of old Henry, Sebastian, William and John. The Harrison Mills burned down and in 1878 were rebuilt by Charles Underhill who made cotton and wool underwear. Samuel Lobsitz took over from Underhill in 1891 and the mills are used today for cleaning and processing wool and cotton.

The Duncan ventures had a dramatic ending when Hicks Arnold and Frederick Constable, New York merchants, took them over to manufacture woolens for their New York department store.